Jesuit-run research center to hold national seminar on inequalities in India

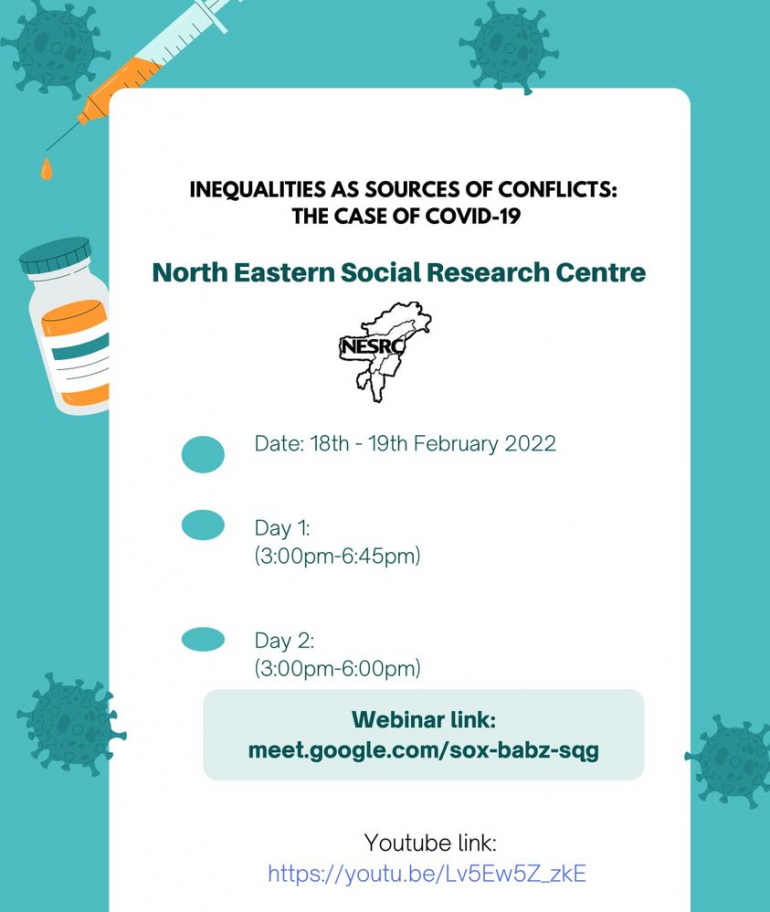

A Jesuit-run research center will hold a national seminar on “Inequalities as sources of conflicts: the case of COVID.”

The virtual event will be organized by North Eastern Social Research Centre (NESRC), Guwahati, Assam on February 18-19, said Jesuit Father Walter Fernandes, director.

The major themes of the seminar would focus on Covid-19, inequalities, migrants, education, economy, health and gender.

A host of scholars and speakers will present research papers and speak at the two-day event.

The causes and dynamics of civil conflicts remain varied, complex, and only partly understood. They are often attributed to factors ranging from rapid social and economic transformations. The pressures of globalization, growing inequalities within states, and the information revolution contribute to inequalities.

“This seminar seeks to focus on inequalities as sources of social conflict in the Indian context. In the past two years, COVID-19 has provided a distinctive vantage point from which many forms of horizontal and vertical inequalities have become apparent, said Fernandes, a noted research scholar and social thinker.

On March 24, 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a complete lockdown from midnight the same day. All transport, offices, factories, other places of work and educational institutions closed down with a four-hour notice. Even a city-state like Singapore gave a three-day notice to its inhabitants to return to their place of origin before declaring a lockdown.

From the beginning, COVID has been caught in political ambitions whether it was Donald Trump’s visit in March 2020 or the flouting of all reasonable norms at the Kumbh Mela (the largest Hindu religious gathering) or massive election rallies before elections to four state assemblies in April 2021. Of importance is the fact that the pandemic exposed and intensified the already existing inequalities in the Indian society, explained Fernandes.

According to the census of India 2011, the country has around 100 million inter-state migrants who have migrated for economic reasons and do unskilled daily wage labourers in the host city.

The dependence of the country’s economy on them is enormous. The sudden lockdown left the migrants with no work and no resources to fall back on, the Jesuit said.

Over ten million migrants walked hundreds of kilometers back to their state. Hundreds of them died on the way lack of food and exhaustion.

Even those who did get home faced initial stigma. Eventually, they may have had to think of alternate livelihood strategies, especially in resource-poor households. Some returned to their pre-Covid places of work, more likely in formal sector jobs, but this is not possible for many.

People from Northeast India also faced compounded racism in other parts of the country, given the broadly accepted theories of Chinese origins of COVID and mainland India’s imagination of a Chinese person into which people from the Northeast “seamlessly fit” (due to physiological features or appearances).

The first wave of COVID was ending in late 2020 after affecting 10 million people and killing 155,000 by official count. Unofficial estimates put the number of the affected and deaths many times higher.

By official count in late November 2021, the number of COVID-19 cases has reached 34.5 million, and 454,000 have died.

One does not know their real number. Obviously, because of the enormity of the pandemic, much of the discourse around COVID has been on medical terms. In the process, its differential impact by caste, class and gender, region has been forgotten. All the field experience and studies show that COVID did not cause inequalities in the Indian social system but intensified existing inequalities.

The pandemic as a disease has made no distinction between the rich and the poor. The picture changes when it comes to damaging social impacts felt more by the poor than by the rich, particularly in the urban slums and the rural and backward areas that are administratively neglected.

The preventive measure of social distancing was possible for the urban middle class and the rural upper classes. But it is a luxury that the urban slum dwellers and the rural poor cannot afford. Rural areas lack the health infrastructure required to deal with such an emergency.

Moreover, no effort was made to educate the rural populations about the need for vaccines. Awareness about it was not strong enough to counter the pandemic.

Glaring disparities became evident in the education and health sectors. When because of the lockdown, schools closed down and education shifted to online classes, the class and urban-rural differences stood out and got intensified.

“Children from the middle class whose parents can afford smartphones and laptops for themselves and even for their children could continue online learning. But, we are yet to comprehend the psychological impact such long-term isolation might have had on children,” said Fernandes.

Rural and other poor children could not even afford the electronic support system. Inequality in learning before the pandemic because of social inequality-based access to schools and learning intensified because of lack of electronic support. Many children seem to have forgotten even what they had learned before COVID-19.

Incidents of child labour and child marriage increased so did domestic violence. The burden of increased domestic work fell directly on women, compounded for many urban middle-class women doing office work from home.

COVID-19 has shown the need for new policies and initiatives to deal with these issues. The government under the influence of the dominant forces of the private sector will not change the policies by itself. It has contributed to compounding the workers’ vulnerability in India through suspension of labour laws and the governments of several States extended the hours of work for factory workers.

They increased the threshold numbers for applying the Factories Act and the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act. A few States went further and took steps to exempt certain factories from the application of labour laws altogether.

Civil society groups have to experiment with new approaches to development, particularly regarding access to basic services. They need to join hands to change policies favoring the marginalized classes, explained Fernandes.

The workshop aims to focus on these and other discussions around inequalities, COVID, its ramifications, and strategies to address the disparities of access that have been made evident in the face of the pandemic and the way forward, with a particular focus on gender, migration, regional specificities and infrastructural availability, he added.

Radio Veritas Asia (RVA), a media platform of the Catholic Church, aims to share Christ. RVA started in 1969 as a continental Catholic radio station to serve Asian countries in their respective local language, thus earning the tag “the Voice of Asian Christianity.” Responding to the emerging context, RVA embraced media platforms to connect with the global Asian audience via its 21 language websites and various social media platforms.