Church as “a sign of contradiction”

After the December 2023 issuance of the declaration Fiducia Supplicans by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, “On the Pastoral Meaning of Blessings,” raucous debate rages, almost revving into overdrive. Accordingly, Pope Francis advised everyone to avoid “rigid ideological positions” in interpreting the pastoral declaration.

While others were thinking of preserving Catholic doctrines and morals, which is also the pope’s intention, the Vicar of Christ takes a more pastoral approach and insists on welcoming “everyone, everyone, everyone.”

The Holy Father emphasized that non-liturgical blessings “do not require moral perfection to be received” and that they are bestowed on the people requesting them, not their union. He explained that “those who vehemently protest [the document] belong to small ideological groups,” while the Catholic Church in Africa presented “a special case” because “for them, homosexuality is something 'ugly' from a cultural point of view.”

Why is there so much polarization? Why is the Church and her pastoral approach in the new millennium so misunderstood, some Catholics were asking?

One explanation is that the Church is “a sign of contradiction.”

Allow me to go back to 1976, when St. Paul VI and the Roman Curia invited Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, later John Paul II (pope and saint), to facilitate the annual Spiritual Exercises for them. Wojtyla gave them 20 meditations, dwelling on the Church as “a sign of contradiction,” all of which “sum up most felicitously the whole truth about Jesus Christ, his mission, and his Church.” The Polish prelate states that the Church, like Christ, remains a sign that prelates within its ranks will oppose.

His emphasis was on the prophecy of Simeon to the Holy Family, “Behold, this child is appointed for the fall and rising of many in Israel, a sign of contradiction” (Luke 2:34). This, I believe, is the one thing we need to remember: That the Church (the Body) as the Sacrament and the visible representation of Jesus (the Head) remain “a sign of contradiction” yesterday, today, and for ages to come.

Take, for instance, the Chair of Peter. This office is a divine institution (Matthew 16:18), but it is also “a sign of contradiction.” Since the time of the first pope, intellectual disputes, arguments, and counter-arguments, with matching blamestorming in ecclesiology, have been going on. God bestows supreme power and universal authority upon a mere human being, the pope, as the Vicar of Christ on earth (cf. Matthew 16:19), making him a sign of contradiction.

A few months before his holy death, retired Benedict XVI (1927–2022) was pensive when he recollected the past. When he addressed the international symposium on “The Ecclesiology of Joseph Ratzinger” held in 2022 at the Franciscan University in Steubenville, Ohio, he made this revelation: “When I began to study theology in January 1946, no one thought of an ecumenical council. When Pope John XXIII announced it, to everyone’s surprise, there were many doubts as to whether it would be meaningful, indeed whether it would be possible at all, to organize the insights and questions into the whole of a conciliar statement and thus to give the Church a direction for its further journey.” That was in 1946, when Ratzinger was still a seminarian.

At this point, it is suitable to reintroduce the term “wreckovation,” which was the derogatory word applied to Catholic architecture after Vatican II. Wreckovation implied a poor style of renovation that certain historic cathedrals and churches have undergone since the 1960s. Critics, mostly ultraconservatives, applied “wreckovation” to Vatican II in the pastoral and spiritual sense. They claimed that Vatican II wreaked havoc on the Church and brought doubts and confusion instead of repairing it.

The gentle German pontiff, a.k.a. Joseph Ratzinger, was one of the most important periti (experts) of Vatican II. From 1962 to 1965, the brilliant Ratzinger attended all four sessions of the council and engaged himself with other council fathers in countless arguments and counterarguments, intellectual disputes, and countless meetings. In 1946, Ratzinger was a seminarian. During Vatican II, he was a peritus, an expert, and in 2022, he was a retired pope. With 76 years in between, the German Pope Emeritus changed his thoughts about Vatican II and made this final statement:

Vatican II was “not only meaningful but necessary.”

Leaders who possess a keen sense of history understand the fundamental causal principle: ignored problems escalate into crises, and unresolved crises eventually transform into scandals. It must be admitted, and admitted humbly, that Church history is full of narratives of scandals precisely because some leaders failed to resolve the crises or just ignored the problems. John XXIII knew this well, so he confronted the problems and crises at their roots when everyone thought otherwise. In his time, Pope Francis did the same thing.

Although divinely instituted, the Church's mystery encompasses its transitory, bureaucratic, human memberships, sins, frailties, and bad judgments, often resulting in global consequences. During the Middle Ages, the Church held significant power as a state religion. As such, the Church rallied her anti-heresy advocacies, witch-hunting campaigns, grand inquisitions, crusades, the Galileo case, the anathemas, and politically-motivated excommunications, all of which became notorious landmarks in world history. In time, the Church has recognized that she was never the societas perfecta she thought she was.

A new direction. Vatican II exposed numerous toxic internal divisions within the hierarchy, intolerable defects, countless personal skirmishes, and other matters that the Church often swept under the rug and concealed from the outside world for pragmatic purposes, primarily to protect its reputation.

In the past, she wanted to protect her reputation, and that mattered a lot to her. Therefore, some bishops may have complicated the series of crises in the past by seemingly covering them up, possibly out of self-preservation. Or “a misplaced concern for the reputation of the Church and the avoidance of scandal,” as Benedict XVI in his 2010 Letter to the Catholics of Ireland suggests.

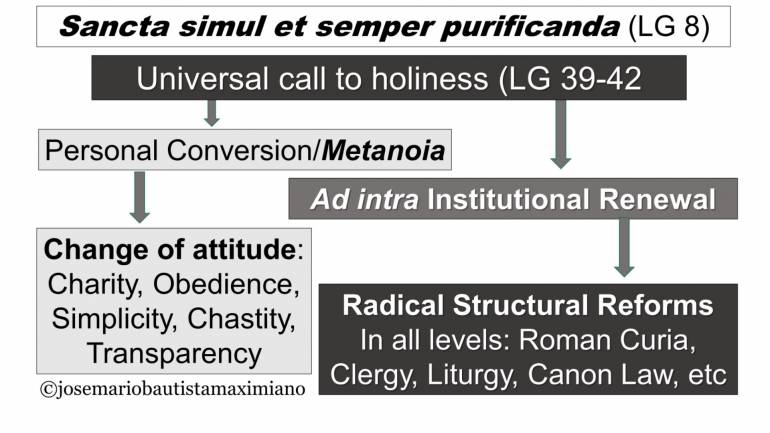

In God’s time, in God’s Kairos, the Church has learned to realize that she is holy and, at the same time, “always in need of being purified,” sancta simul et semper purificanda (Lumen Gentium, 8). The Church has come of age, fully aware that the all-encompassing inclusion of sinners is the inevitable factor behind ecclesiastical crises and abuses and that her desire to embrace in her bosom both sinners and saints. That she intends to be a tent hospital in the new millennium, welcoming “everyone, everyone, everyone” (in the vision of Pope Francis), is a big part of her mystery.

Since Vatican II, the Church has been heading in a new direction: the Ecclesia semper purificanda leads to constant reforms (semper reformanda) so that she becomes a Church that “always follows the way of penitence and renewal” (Lumen gentium, 8).

Face-to-face with the new challenges of the times, Pope Francis was obliged to champion big changes and was compelled to overhaul the central government of the Church, without calling for Vatican Council III. He contemplated the situation with the intensity of a pilot navigating through a turbulent storm.

Under his leadership, the Church, like the phoenix, rises from the ashes of crises and scandals. Her resolve to always purify and reform herself is indeed a work in progress until the Parousia.

With the “New Evangelization” pursued with dynamism and audacity, with a more transparent governance in place, with the pastoral office armed with its canonical authority being renovated, and her canon law being amended for pastoral effectiveness, she remains the visible and historical presence of Christ on earth, the one holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church, until the end of time.

*Dr. José Mario Bautista Maximiano is the author of Church Reforms 2 (Claretians, 2024).

Radio Veritas Asia (RVA), a media platform of the Catholic Church, aims to share Christ. RVA started in 1969 as a continental Catholic radio station to serve Asian countries in their respective local language, thus earning the tag “the Voice of Asian Christianity.” Responding to the emerging context, RVA embraced media platforms to connect with the global Asian audience via its 21 language websites and various social media platforms.